The Bilingual Target: Rising Demand for English Proficiency in Latin America

During the past decade, Latin America’s governments have prioritised education reforms and more specifically the improvement of English language skills as a step to ameliorate economic conditions within the countries. A report by Education First (EF) shows that youngsters’ command of English is close to the respective global average. Adults’ competences, however, are what remains very weak.

In the last three years, there have been various initiatives to enhance the language expertise in a way that would help students and professionals actively participate in global economy processes. An example of this is the Chilean English Opens Doors Program, which invites volunteers to teach independent classes in public schools to students aged between 10 to 18 years old. They not only support them in improving their English, but also participate in cross-cultural exchange to help broaden their views on the world. Tutors have the freedom to choose a particular extracurricular activity to lead, varying from camps and debates to public speaking events and spelling bee competitions. Participation in the program is free and volunteers are encouraged to act as ambassadors of their home country, empower students and create a stimulating environment to make a worthwhile impact on the local community.

Panama is another country in the region that demonstrates a significant increase in the number of English speakers during the past couple of years. In fact, it is the country where proficiency in the language has seen the best improvement in this area worldwide due to its bilingual program. The Panama Bilingual Program was launched in 2014 with the objective to prepare Panamanians for the competitive global job market by perfecting their English language skills. The program aims to train 25,000 bilingual teachers and 260,000 bilingual students over the next four years.

On the other side, according to a recent research by the British Council, Peru is a country where indigenous languages have been historically prioritized over English in order to protect local languages and preserve the country’s cultural and historical specifics. Nowadays, recognizing that English is crucial to the Peru’s progress and development and also essential from the perspective of employers, the government plans to achieve bilingualism with English as the priority language by 2021. Funding has already been allocated to meet the set targets and during 2015 the government almost doubled financing for the education sector. As part of the National English Plan, the objective to be reached by 2021 is for all 8,500 Peruvian public secondary schools to have a 45-hour teaching week. The UK has also suggested measures to assist with teachers’ training, help with curriculums and methods and initiatives to increase student mobility between the two countries.

Another interesting case, observed by the EF report is that of Mexico. Although someone might think that its proximity and very well developed economic relationships with the US would mean that the population has excellent English language capabilities, the facts show that proficiency levels among adults are not very high. Following the US-Mexico Bilateral Forum on Higher Education, Innovation and Research in 2013, the countries have discussed to expand mutual opportunities for educational exchanges, scientific research partnerships and cross-border innovation. A part of this initiative is the Mexico Proyecta 100,000 program which aims to send 100,000 Mexican students to the US for short-term intensive language courses and receive 50,000 American students by 2018.

In an unprecedented effort, the government of Mexico awarded 7,500 SEP-SRE Proyecta 100,000 scholarships for short-term intensive English language courses for underserved students and teachers (59% women).

The Bilateral Forum was followed by a series of workshops, bringing together government, academia, civil society and the private sector to set up an Action Plan divided into four pillars: Academic Mobility, Language Acquisition, Workforce Development and Joint Research and Innovation. Further programs to enhance mobility, language training and education cooperation are the Fulbright-Garcia Robles program, EducationUSA educational advising services and various teacher exchanges.

Brazil has also recognized the role of English proficiency in developing its future workforce and maintaining the position of a global economic power. In 2013 the Brazilian Ministry of Education launched the English Without Borders program, renamed to Languages Without Borders a year later, with the primary goal to provide support for university students wishing to study abroad through the Science Without Borders program. Besides English, the current scheme covers seven additional languages, including Mandarin and Japanese in order to help students to be successful in their foreign experience.

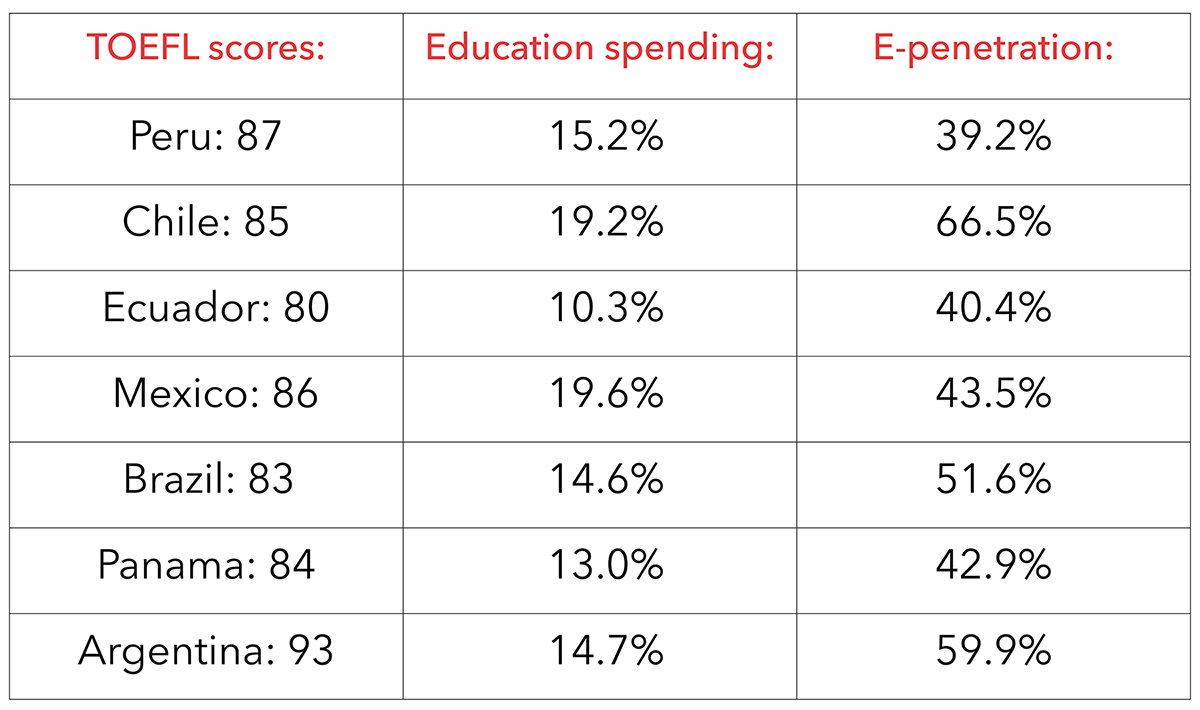

In general, the report by EF views Latin America as the region with the most improvements regarding the English proficiency level worldwide. The only country that demonstrated a downward trend is Colombia and the one with the best proficiency, similar to European averages, and also the one with highest TOEFL scores globally is Argentina. A noticeable trend is that the majority of the nations have launched governmental programs stimulating English language skills during the past three years as a means to strengthen international partnerships and progress on the global economy scene.

(Source: Education First)